Everyone knows what a bumble bee is. – Right? Right?! – Every child has an intuitive sense of what a “bee” is, and will draw you a cute black and yellow winged blob flying between flowers. But as we get older, most people become less certain. For good reasons. Insects are so diverse! Is any black and yellow buzzing thing a bee? Are all of them black and yellow? Anyone can be forgiven for being a bit uncertain about what is, and what is not, a bumble bee. Let’s remedy that confusion with some details on the bumblebees of eastern North America.

Bumble bees are remarkable animals. They are social insects that cooperate to raise their offspring — or more often their younger sisters and a few half-brothers. They have an almost entirely vegan diet, subsisting on the pollen and nectar they collect from flowers. They are essentially warm-blooded, using energy stored in their body to warm themselves up on cold mornings. These features make them critical pollinators, especially in colder northern temperate and boreal ecosystems where they are some of the most active pollinators. They provide critical services to reproduction of wild plants, as well as to many human crops. Despite their importance, for reasons we don’t quite understand, they have also been facing a crisis of declining populations.

Bee basics

Before we get to bumble bees, let’s consider what we mean when we refer to bees. Bees are flying insects closely related to ants and wasps. There are thousands of species of bees around the world. What distinguishes them from wasps and ants is rather technical: the fuzzy hairs that cover their bodies are branched. This may seem a bit trivial, but it’s been part of the key to their evolutionary and ecological success. The branched hairs help them gather up pollen from the flowers they visit, making them very good at gathering up this food source. It’s thought that the first bees evolved from wasp-like ancestors some time before the extinction of most dinosaurs. (Non-avian dinosaurs became extinct about 66 million years ago. Some dinosaurs do continue to exist, in the form of birds).

Things that are not bees

So if not every yellow and black insect is a bee, let’s take a moment to briefly introduce what those other critters are.

Hoverflies: With classic yellow and black stripes hoverflies are probably the insects most frequently mistaken for bees. Compared the bees, flies have eyes that take up most of their heads. They also have a small pair of balancing organs just behind their wings. Hoverflies are also much more nimble fliers than most bees. Male hoverflies give the group their name, since hovering stationary in midair is how they attract mates. Hoverflies are also excellent pollinators. They have no sting, and so they’re harmless to humans. Adult hoverflies feed on nectar from flowers, but their juveniles can be active and voracious predators of pests, especially aphids.

Wasps: Wasps are closely related to bees, and share their ability to sting. But wasps lack the defining branched hairs of true bees. Wasps can be distinguished by their narrow waist, more pointed abdomen, and by the fact that they are usually not as hairy as bees. However, wasps are also a very diverse group of insects. Some are social, others are solitary. Some are predatory, while others are exclusively pollinators that feed on pollen and nectar. In general, wasps are very beneficial insects. Besides pollination, many wasps will eat nuisance insects such as mosquitos, aphids and flies.

Some moths, beetles, and other flies also try to pass themselves off as bees. This can make identifications of bees difficult for people who are unfamiliar with insects. In general these more distantly related mimics only wear bee colors, while their general anatomy conforms to their actual taxonomical group. For example, the snowberry clearwing pictured here has the coiled proboscis (the drinking-straw mouthparts) that most butterflies and moths have. And bee-mimicking beetles have tough shell (the elytra) characteristic of most beetles. And flies — hover flies, robber flies or bee flies – all have large eyes and balancing organs behind their wings.

To understand why so many insects converge on the same coloration as bees, read below about the venomous sting of bees and how it’s announced to the world.

Social bees

Some groups of bees are solitary, meaning that, like house cats, each individual of the species is mostly concerned with their own needs and with providing for their own offspring. Common examples of solitary bees include the wood-munching carpenter bees and the mason bees and leaf cutter bees which are important pollinators of crops like apples and alfalfa.

The most numerous and successful groups of bees are social. In biology, this terms means something slightly different than the word’s meaning in everyday use. Social insects don’t have language or culture the way the humans do. Instead animals are described as social if adults cooperate to raise offspring. Many animals do this. Prairie dogs and meerkats will cooperate to look out for predators. Some spiders will cooperate to make huge webs where they all lay their eggs. Even some wasps, like paper wasps, share a nest built by several adults and share the duties of gathering food for the offspring they all produce. Some bees take social cooperation a step further. They divide the tasks of the social group (the colony or hive) up so that some individuals only ever gather food – these are called foragers – while one individual – the queen – produces offspring. There is a spectrum of variation among different bees species, with some showing very sharply divided caste roles – honeybees are an extreme example of social insects – while others are more tentative in their degree of cooperation. Biologists are keenly interested in this variation because of what it can tell us about the evolutionary utility of cooperation and because it reflects on humanity’s unique mixture of social cooperation and conflict.

Don’t they sting!?

Bees horde a valuable resource: the pollen and nectar they have collected from flowers. This is used as food for their babies, and to get them through lean times, like the winter or the dry season. Some wasps collect more gruesome food in their pantry. They paralyze other insects or spiders, that they will feed to their hungry babies. Insects haven’t (yet) invented refrigeration. So the best way to keep food fresh is to keep to alive. Whether it’s vegan or paleo, a lot of effort goes into collecting this food. So it’s helpful to be able to defend it. Like nervous preppers or survialists, bees are interested in defending their cache of resources. And evolution has provided them with an excellent weapon. The creepy wasps that paralyze their food do so by injecting a paralytic venom into their prey using needle-like structure at the end of their abdomen. We know this as the stinger. Even bees that have evolved to eat pollen and nectar have retained the stinger as a means of defense. They no longer need it to collect food, but the sting can be used to fend off potential predators. Most bees and wasps are quite capable of stinging repeatedly without harming themselves. Many people know that honeybees can die as they stink a person. This doesn’t happen all the time, and it requires relatively thick skin. But the honeybee’s stinger is barbed, allow it to hang on and providing more time to inject venom. The side effect is that the bee risks getting stuck and injuring itself. Honeybees are an extreme case. Because there can be tens of thousands worker bees – who will never produce offspring – in a hive, each individual’s evolutionary success is essentially a matter of how well the hive does as a group. Over the ages, honeybee hives with workers delivering a more potent sting have done better — even when that potent sting sometimes leads to the death of some worker bees. In an evolutionary sense, we have ourselves to blame for this. Large mammals, including humans, have been honeybees most serious predators over the ages. An effective way for a small insect to defend itself against such a large predator is to team up by being social, and getting ready to sting.

The irony is that while many bees can sting, most won’t do it unless provoked. (As I said before, honeybees are extreme!) Most bees don’t live in such huge hives, and individuals, even non-reproductive worker bees, are too valuable to the group to sell their lives too easily. For example, while bumble bee stings that are similar in their painfulness to honey bee stings, individual bumble bees are much less apt to sting a person. If a bumble bee is provoked, for example by a person disturbing their nest, they can sting repeatedly. However, bumble bees are not killed by stinging. Their stings are not barbed, and they are capable of stinging until you get their message: run away, human!

Bottom line here: don’t mess with a bee and it (probably) won’t mess with you.

Okay, I’ve just been stung! What do I do?

If you know you have an allergy to honeybee stings, you should follow the advice of your doctor. Usually this involves carrying an Epi-Pen. Follow the instructions on how to use it. Call 911 if you have trouble breathing. Place someone in shock on the floor, on their side.

Most people are not adversely affected by stings from bees or wasps. But it can hurt like the Dickens. If you only see local swelling and have no issue with heart rate or breathing, then there should be little cause for alarm. Treat the area of the sting with cold and an NSAID. Try not to scratch the site of the sting, as this can break the skin and lead to infection.

What’s the point of being venomous if nobody notices?

Any physical conflict comes with risks. Even if a bee can sting, just getting into a tousle with another animal brings the danger of injury. Wouldn’t it be better if the bee could advertise that they are dangerous, without having to prove it? That’s what the black and yellow coloration does. This is what biologists call aposematic coloration. The contrast of black with a light color like yellow, red or white is meant to be noticeable and memorable to other animals. If another animal is naive and provokes a bee, it will sting, and that animal will associate the memory of the painful sting with the distinct coloration of the bee. Many other animals also advertise venom with contrasting colors, including snakes, spiders, and even octopus. Similarly, skunks advertise their awful smell with their distinctive black and white coloration.

Different bumble bee species have different variations on the theme of contrasting colors, but there is often convergence of patterns within a geographic region. For example, bumble bees in Europe tend to be mostly black with highlights of red, white or “buff” as they like to call tan in the UK. While in eastern North America, most bumble bees are black and yellow, with a few species adding in some red. This consistency means that individuals carry less risk. They share the risk burden of training naive potential predators. This evolutionary convergence in warning coloration is called Müllerian mimicry, named for Fritz Müller, a 19th century biologist who first described this tendency.

Sit in a meadow, and watch fat, slow bumble bees go about their business. All the while, hungry birds will be searching for hidden caterpillars or flying acrobatically to catch quickly flying insects. Aposematism works really well as a protection for the bees! It works so well, that some insects cheat the system. — They wear the warning colors, when they are, in fact, totally harmless and delicious. (Well, I assume they’re delicious. I haven’t tried.)

Male bees have no stinger and make no venom. They are anatomically incapable of stinging. But they have color patterns very similar to their venomous sisters. Some male bees will even mime the stinging motion, jabbing their harmless posterior into your hand if you catch them. Male bees enjoy the protection provided by their colors, when it’s only female bees that can train would-be predators. Male and female bees are after all, both bees. But the abuse of the aposematic system doesn’t stop there.

Plenty of completely unrelated species have evolved to mimic the aposematic warning colors of bees. Insects like hover flies are harmless. They don’t have a stinger. But they mimic the colors (and sometimes the shapes) of bees or wasps to gain the same aversion that potential predators associate with bees. The mimicry of venomous of toxic animals by harmless ones is called Batesian mimicry, named after — you guessed it — Henry Walter Bates, a 19th century biologist who described this evolutionary pattern.

What’s special about bumble bees?

This is a page about bumble bees, remember? So what makes them so special? Well, by now hopefully you’re pretty impressed by bees in general. But bumble bees really are unique. Bumble bees have evolved to exploit a niche that very few insects have ever explored: the cold.

For any organism, being alive and doing things depends on hundreds of thousands of chemical reactions. Even if you’re sitting quietly reading these words, your cells are hard at work converting the light falling on your eyes into nerve signals, passing those signals across your brain. If you move, it requires chemical reactions in your muscles. Just to stay alive, every cell in your body constantly needs to extract chemical energy from the oxygen that you breathe in. All these reactions happen faster at higher temperatures. Most animals are ectotherms, meaning that their body temperature is dependent on the temperature of the environment around them. Therefore they are able to do more, faster if temperatures are higher. When it’s cold, they are typically slower. Some animals are endotherms. They use some of the energy they get from food to heat their body above the temperature of their surroundings. Humans are endotherms, and maintain a nearly constant body temperature (about 37˚C or 97.5˚F). Bumblebees are able to turn their internal heaters on and off at will. They can generate heat to warm their flight muscles, allowing them to fly even on days that would keep most insects slow and sluggish. Thermoregulation and hairy bodies help adapt bumble bees to colder climates.

Being active at low temperatures makes bumble bees essential pollinators in colder climates, like Canada and the northern United States. However, they have some other specializations that makes them superb pollinators. First, bumble bee species and individuals vary widely in size. This means that different individuals can specialize in pollinating different flowers. Individual bees learn which flowers they are best suited to and focus on bringing home the pollen and/or nectar they are best at. If a bumble bee specializes in foraging on certain types of flowers, she will also have the ability to literally buzz the pollen free from the flower. It’s like a sonic death ray! Well, without the death. More like a sonic food-gathering ray. But still amazing. Buzz pollination gives bumble bees a huge advantage in efficiency over other pollinators. In fact, this is the trait that gives bumble bees their Latin name, Bombus, which means “humming”.

Live fast. Die young.

So bumble bees are pretty awesome, right? They’re venomous. They work in cooperative groups. They collect food using sonic super powers. They’re smart. They can even be warm-blooded. How do they not rule the world? Well, it takes a lot of energy to do all those things. Bumble bees live a precarious life style. If they use all their many skills – and if they’re lucky – a few of them will get to survive until the next year.

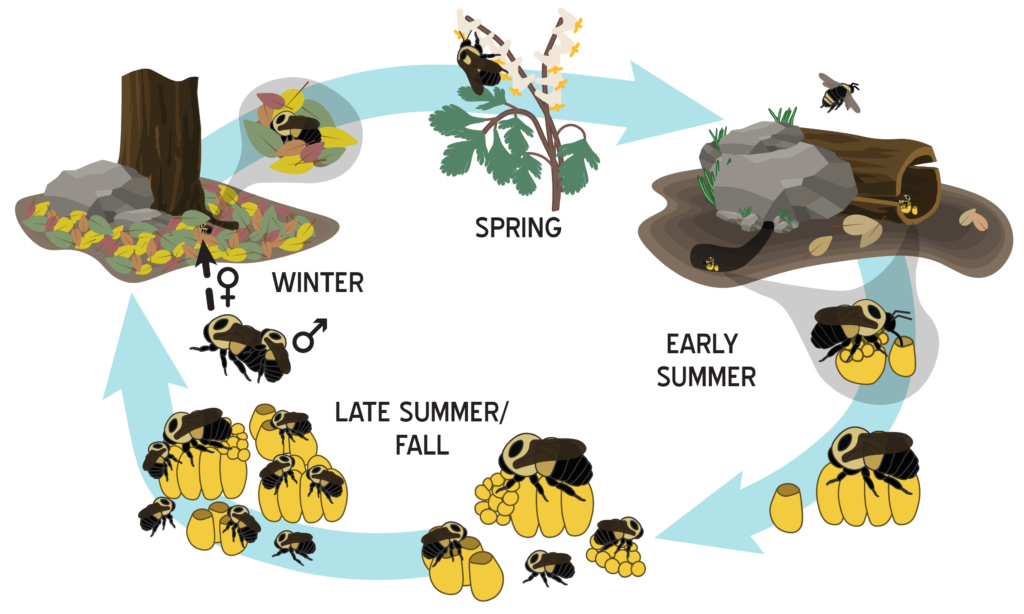

Bumble bee queens hibernate through the winter in tiny chambers they dig in loose soil or in dry leaves. They will dig themselves out as the weather warms. Initially, they live life like a solitary wasp would. Looking out for their own immediate needs. First up: find food. Often this will be nectar from early flowering trees, like red maple. Later they will visit other flowers as they emerge and provide nectar and pollen. The queen’s next task is to find somewhere to build a nest, a safe place for her offspring to grow up. Bumble bees like to nest in dark, dry places. But different species have preferences for old tree trunks, the base of grassy tussocks, or abandoned rodent holes. Some will even nest in the walls of old barns, sheds or houses. In spring, you will often see big queen bumble bees flying low to the ground. They may stop and walk around a depression or hole in the ground, trying to evaluate the real estate. Once she finds a suitable nest site, the queen will make something called bee bread, a mix of pollen and regurgitated nectar – hey, that’s basically honey – and lay her first eggs on it.

Wait! – How’d she lay eggs without a male bee coming into this story? – Well, bumble bees, like many insects, have the ability for females to store sperm from males they’ve mated with long ago. In this case, a female will fertilize her eggs with sperm from a male she encountered in the late summer or fall, before she entered hibernation.

After laying her first eggs, a queen bee needs to maintain a delicate balance. Her eggs will develop faster if she stays sits on them and uses her endothermic ability to create heat to warm them. In places like the high arctic, this is essential to their survival. However, as she stays there, warming her eggs, she runs the risk of starving herself. Occasionally, she will need to pop out to find her own food, or they’ll all die. Once the eggs hatch, the juvenile bees are still pretty helpless. The most they can do is eat the bee bread that been stashed there for them. Meanwhile, the queen will build the first wax cells in the nest and move the juvenile bees into them, along with more bee bread. Like honey bees, bumble bees have a gland that secretes wax, which they shape into bee-shaped cells using their mandibles. As the juveniles grow, they will eventually metamorphose into an adult bee. From egg to adult takes 4-5 weeks depending on the species and temperature.

At this point, a solitary wasp would have just completed its life cycle, as the new adults would fly off, mate and start their own nests. However, bumble bees are social. The first group of offspring will cooperate as a colony. They forage for nectar or pollen, bringing it back to the nest to feed younger siblings. Meanwhile, the queen will no longer venture out. She will stay in the colony for the rest of her life, eating food her daughters bring home, laying eggs, and if necessary defending herself from challenges to her position as queen.

During the warm months of the year, the bumble bee colony will grow, as it collects more food and adds more workers. Eventually however, if their genes are to be passed on, they will need to produce bees capable of reproduction. Queen bees can control the sex of their offspring. Male bees are haploid. They arise from eggs that are not fertilized by sperm. (So technically, male bees have a mother, but no father. Weird, right?) Worker bees are female, just like the queen.

The difference between workers and queens varies in different bee species. In social wasps, like paper wasps, many females share a nest. They are anatomically very similar. Each one is capable of producing eggs and acting as queen. But a social order among them determines who lays eggs and who forages. Paper wasps are constantly challenging one another to determine this hierarchy, and a wasp that starts as a forager can later become “queen”. At the other end of the social spectrum are honey bees, where queens are marked from early juvenile stages by being fed a special food and given extra space to grow. Honeybee workers are also female, but they are never capable of producing offspring. Bumble bees are intermediate between these social extremes.

Bumble bee workers tend to be smaller than queens, but many of them are capable of producing eggs under some circumstances. (More on that later.) It’s actually the workers that control whether female eggs will be allowed to develop as workers or new queens, called gynes. They do this in part by controlling the diet of the juveniles and in part by controlling the size of the cells the eggs are laid in (by the queen). The queen can also choose how many males she thinks the colony should produce versus new female offspring (workers or gynes).

Adult male bees do relatively little work in the colony. In some species they help incubate new eggs, but in other species males just eat and take up space. In either case, the workers evict them from the colony within a few days. From then on, their role in life is to fly away, carrying half their mother’s genes, to share with a new gyne, recently emerged from a different colony. Males are often fuzzier and have larger eyes than females, and in many North American species they also have more yellow, especially on their face. But they usually have the overall pigmentation pattern of the females of their species. Male bumble bees are on their own in the world. They must find their own nectar and spend the cold nights alone. You can often find male bumble bees on flowers in the later summer and fall, especially in the early morning before the sun has helped to warm them. They conserve their limited resources and don’t use endothermic heating as much as their sisters. Bumble bees mate while in flight, where they use their large eyes to find gynes. Occasionally you can find a pair who has fallen to the ground before going their separate ways. After the male has delivered sperm to the female, he will continue looking for other gynes. But eventually, when the weather starts to freeze, he will die. After the new queen has mated, she will find loose soil and dig herself in for hibernation. Only hibernating young queens will survive the winter.

Winter Is Coming

Back in the colony, the year ends in chaos of epic proportions. Once the queen starts to produce male offspring, the workers reach the end of their willingness to cooperate. Up until that point, they have been helping their mother and their sisters, who all share half their genes. But the males produced by the queen only share, on average, a quarter of the genes of each worker. For a sterile worker to help raise her sisters, it’s genetically equivalent to raising their own offspring. But their nephews don’t stack up in that way. The workers’ reaction is to start producing their own male offspring. Remember, workers have never mated, so they can’t fertilize eggs to make female offspring. But they can produce males from unfertilized eggs. Soon, many of the larger female workers in the colony will be making male offspring. Sometimes they fight with each other over stored pollen and honey and even kill the male eggs laid by other females in the nest. Some male bees do make it out of the colony under these chaotic conditions. These males will have the chance to pass on their genes if they can find a new queen to mate with. However, as winter sets in, all the bees in the colony will eventually freeze to death.

All this bumble bee activity: flying, buzz pollinating, making heat to warm muscle and incubating eggs. It all takes energy. At the year’s end, the nest, all its honey and bee bread, the queen and all the workers, will perish. If a colony has been successful then they will have sent off many well-fed, heathy gynes who will emerge to start the cycle again next spring. All their silent hopes rest with the next queens sleeping in tiny chambers just below ground.

Want to learn more?

Check out these resources!

- Send us your bumble bee sightings!

- Check out our bumble bee species identification guides for northeastern North America (letter size, or legal size with a few more details)

- The Bugs in our Backyard book list has lots of titles related to bees

- Bumble Bee Watch (North America)

- Bumblebee Conservation Trust (UK)