Humans aren’t the only ones who have been enjoying New England’s distinctively warm winter this year. For the invasive winter moth Operophtera brumata warm weather could really heat up the mating season for these heart-shaped forest destroyers. According to arborist Mike Duddy, the invasive species, originally from Europe, was responsible for defoliating 10,000 acres over the course of last year in Maine’s Cumberland County alone. The species has the capability to infest a wide range of plants, from oaks and maples to aspens and blueberry bushes. However, considering how little we know about the winter moths and their distribution, it is difficult to predict the full potential impact of the invasion.

The winter moths were first observed in Massachusetts in the early 2000s and have steadily spread south into Rhode Island and north along the Maine coast. However, New England isn’t the only region that has been subjected to the moth’s invasion. Nova Scotia, British Columbia, and the Northwest United States have also dealt with winter moth infestations. Taking a page out of Nova Scotia’s book, the forest service began releasing parasitoid flies along the southern coast of Maine in hopes these predators may combat the expanding invasion.

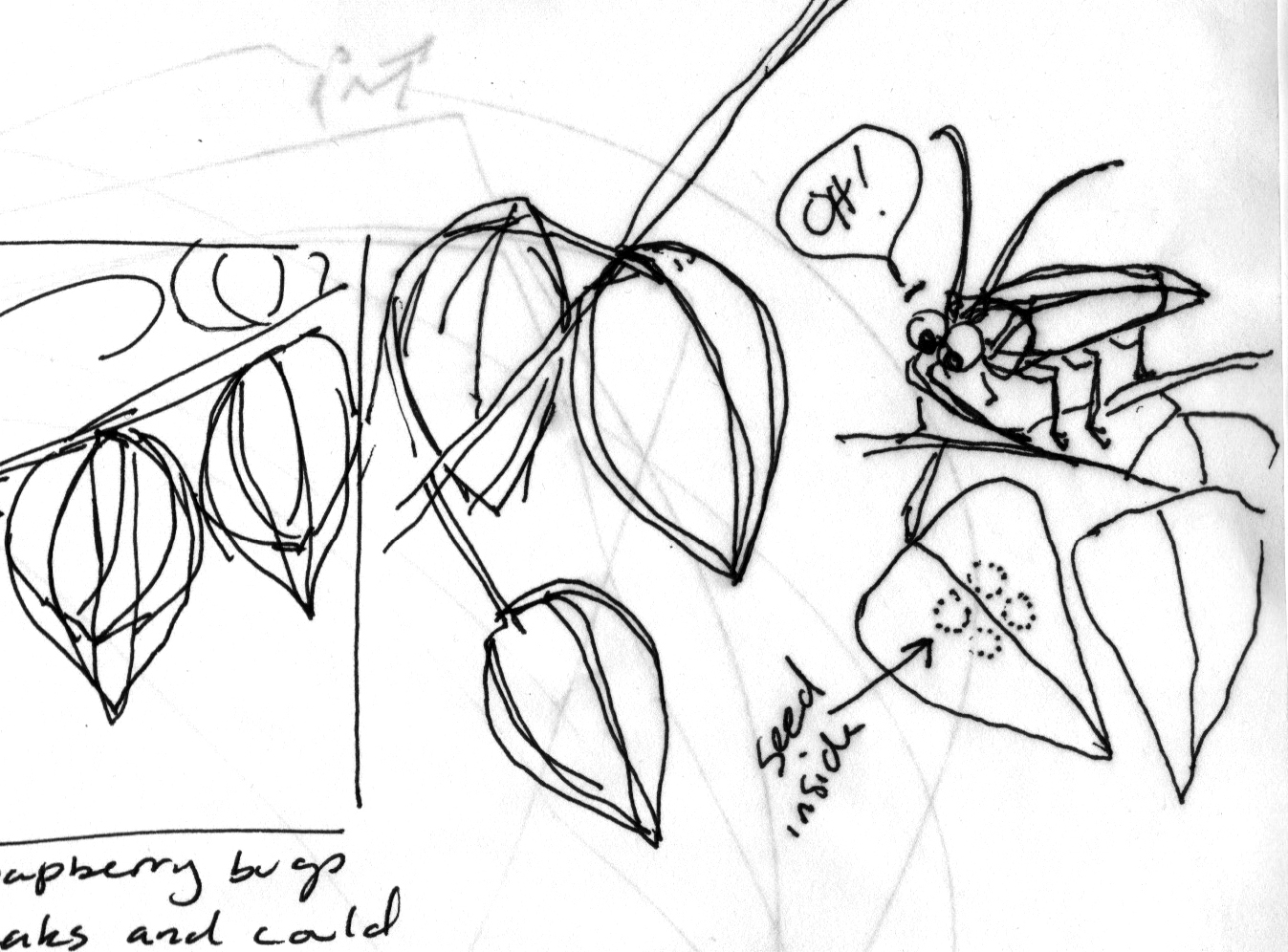

Winter moths have a life cycle that makes them stand out. They get their name because adult males emerge from underground pupae in November or December when there aren’t many active insects around in New England. They can be found mobbing lights after Thanksgiving dinners in places like Massachusetts. Females have wings that are too short to support them in flight. Instead they climb up trees, where it’s up to the males to find them by smelling for their distinctive pheromones. After mating, females lay eggs in crevices or under loose bark, where the eggs will stay until the warmth of spring. Hatchlings release a long line of silk and let the wind carry them into high treetops. After ballooning into the canopy, the caterpillar eat the buds of early flowers and leaves, which is why they cause such devastation to forests. Winter moth caterpillars resemble inchworms. (Both inchworms and winter moths are members of the family Geometridae.) By early summer, the caterpillars climb down to pupate in the soil, and the cycle starts again.

The winter moth’s life cycle exploits times when it’s typically too cold for most insects, early winter and early spring. With climate change making northern winters more mild, it’s feared that this will only make life easier for Operophtera. As average temperatures rise with global warming and this species continues its range expansion, many of us may be seeing more of the winter moth.

Wondering how you can help? The Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry has released a short winter moth survey for 2016. (Go citizen science!) By keeping an eye out, you can help conservationists track the movements and density of this detrimental species along the Maine coast. Data from the survey will be used to better understand hatching patterns of the species and to develop better biological control strategies. In the next few years, it will be especially important to monitor northward range expansion of winter moths, especially considering the impact this invasive could have on the state’s eight billion dollar forest industry, which is concentrated up-state. The winter moth represents only one of many invasive species that have reaped the benefits of climate change and moved up north to Vacationland.

Since it’s Valentine’s Day, remember: if you’re really digging at the bottom of the barrel for date ideas, try to familiarize yourself with local invasive species, then find out what you can do to help!