When you think of zombies, shambling, flesh-hungry creeps may come to mind. As we’ve been taught by shows like The Walking Dead, zombies often travel in giant hordes that can be smelled from miles away. And while the prospect of roving packs of decomposing bodies is pretty frightening, the natural world has one of its own zombie animals much weirder than anything in human fiction.

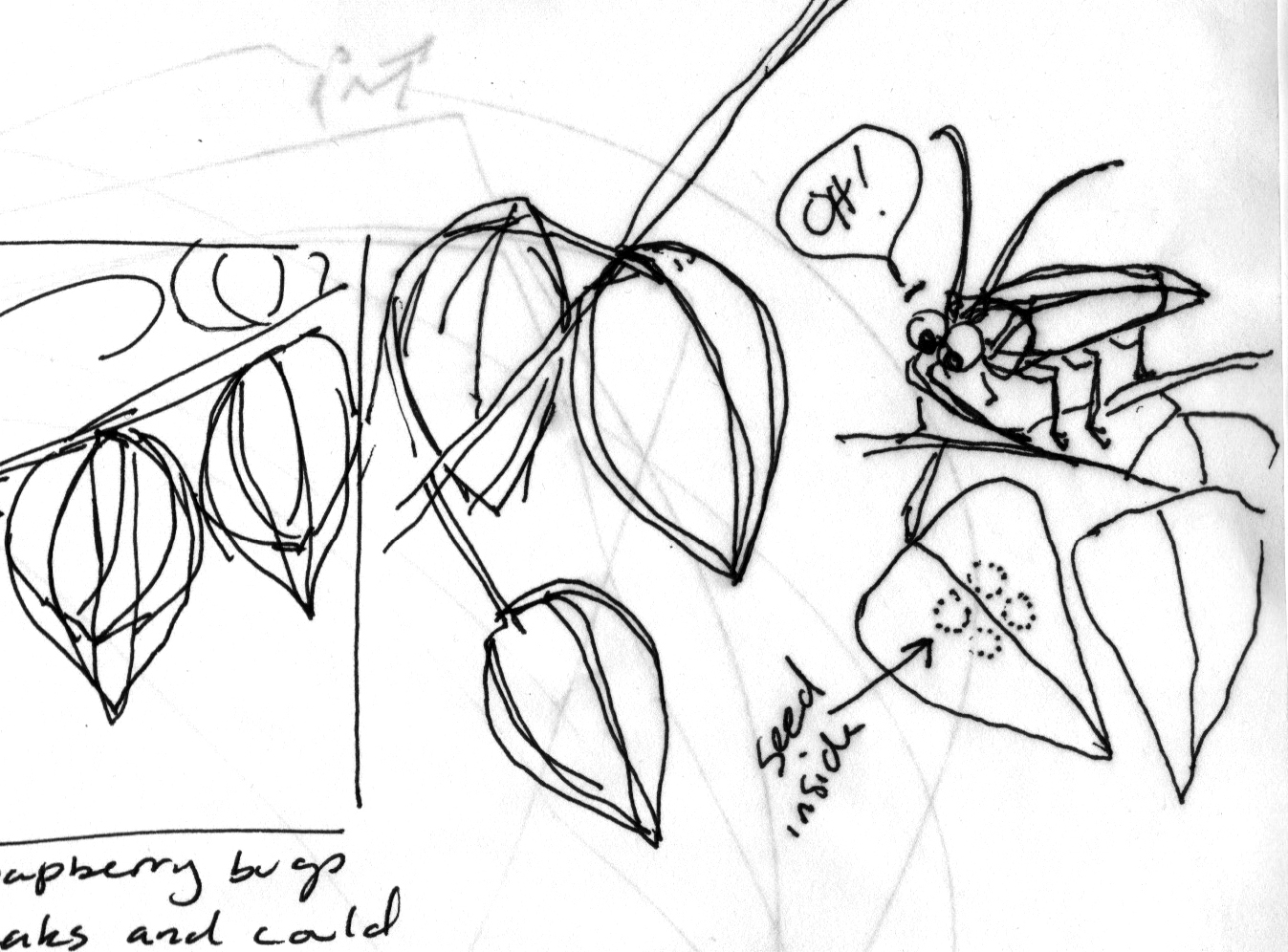

The stage is set in the rainforests of Brazil as carpenter ants go about their usual busy days. All is well, except that one individual (and possibly more) of the colony has been compromised. Somewhere on the cuticle (most external body coating) of a particular ant, a small invader is poised for attack. The interloper is a spore of the fungus Ophiocordyceps unilateralis, which uses special enzymes and built-up mechanical pressure to break through the complex exoskeleton of the insect1. Once inside, the spore begins to bud off and send bits of itself throughout the body of the ant. What begins as a single celled invasion quickly grows into a network of interconnected fungal fibers, or hyphae. By the end of a three week period, almost half of the weight of the infected ant is fungus2! Once an ant has fully succumbed to the microbial onslaught, it leaves the colony and heads for the underside of a leaf. Finding a spot with just the right humidity and temperature for fungal growth, the ant bites down onto the prominent mid-vein of a leaf and perishes, a behavior often called “the death grip”. Afterwards, a large spike, named a stroma, explodes out of the head of the ant. Mature spores rain down from the stroma onto the forest floor, infected any ants passing by and starting the cycle of infection all over again1.

Previously it was believed that the O. unilateralis infected the ant’s brain in order to manipulate its host. But recent studies have shown that while a remarkable amount of hyphae penetrate the muscle fibers inside the ant, the brain is left intact3. This finding has led researchers to liken the odd behavior of the ant to a puppeteer manipulating the strings of a marionette.

Scientists have found evidence that this complex interaction between parasite and ant has been going on for a very long time. Fossil leaves that have been dated to about 47 million years ago show bite marks similar to the “death grip” of modern ants infected by O. unilateralis. This leads some scientists to believe that this interaction is one of the oldest parasite-host relationships in the fossil record4.

References:

- Evans, H. C., Elliot, S. L. & Hughes, D. P. Ophiocordyceps unilateralis. Commun Integr Biol 4, 598–602 (2011).

- Hughes, D. P. et al. Behavioral mechanisms and morphological symptoms of zombie ants dying from fungal infection. BMC Ecology 11, 13 (2011).

- Fredericksen, M. A. et al. Three-dimensional visualization and a deep-learning model reveal complex fungal parasite networks in behaviorally manipulated ants. PNAS 201711673 (2017).

- Hughes, D. P., Wappler, T. & Labandeira, C. C. Ancient death-grip leaf scars reveal ant–fungal parasitism. Biology Letters 7, 67–70 (2011).