Our lab group is well-acquainted with the red-shouldered soapberry bug, Jadera haematoloma. However, there are a variety of true bugs in the United States that look like the red-shouldered soapberry bug and occupy similar environments. For example, have you ever heard of the soapberry bug’s distant relative Dysdercus andreae also known as the St. Andrew cotton strainer?

On a recent adventure to the U.S. Virgin Islands, a mass of St. Andrew cotton stainers were found scattered across the sandy shore of Genti Bay. Like the red-shouldered soapberry bug, this cotton stainer species is in the order Heteroptera and uses a long beak for eating. Their habitat ranges from the Caribbean up to the coast of Florida, and this species can be identified by their distinct white diagonal lines on the hemelytra of the bug.

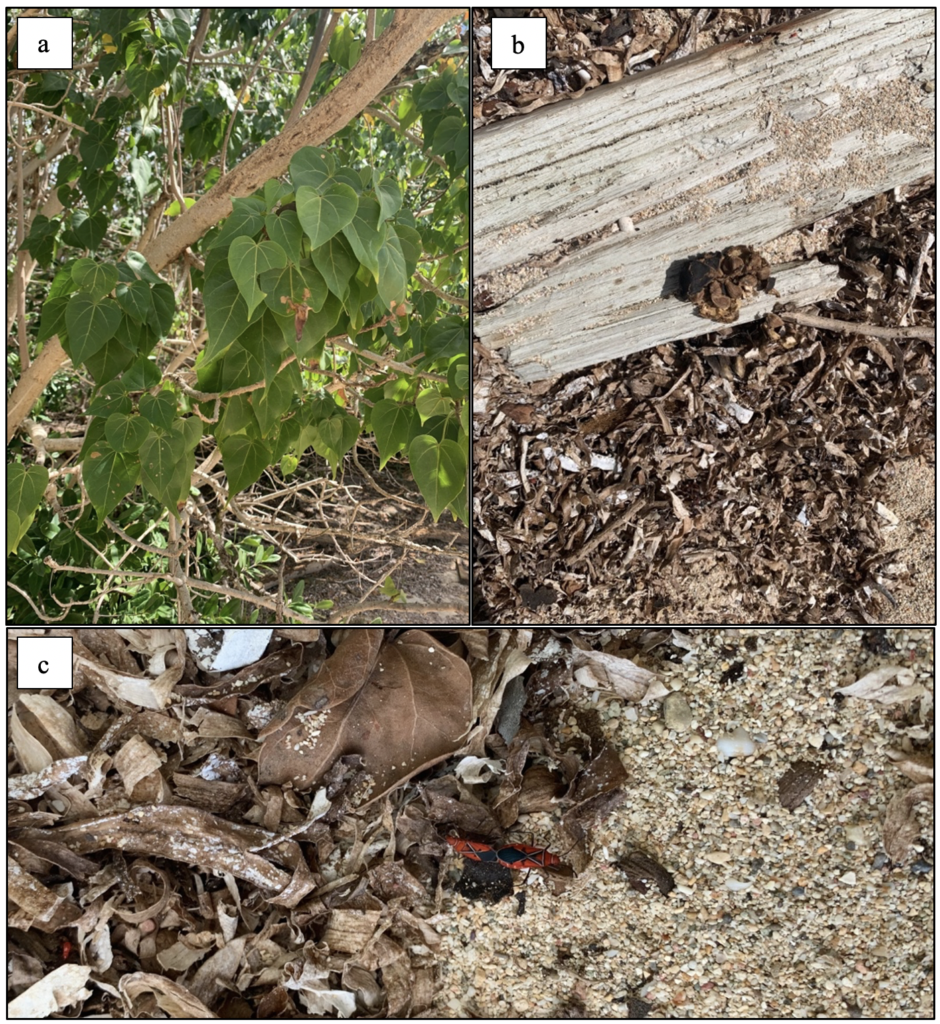

While red-shouldered soapberry bugs and St. Andrew cotton stainers both exist in similar environments, their habitats do not overlap due to niche differentiation, and their occupation of different microhabitats. Niche differentiation is when species avoid competition by finding different ways to use the environment, allowing them to coexist. For example, the red-shouldered soapberry bug feeds on balloon vine and golden rain tree seeds. On the other hand, St. Andrew cotton stainers feed on fruit on Portia trees. This difference allows the two bugs to coexist in overlapping locations by occupying different microhabitats.

At Genti Bay, St. Andrew cotton stainers gathered on top of many leathery seed pods of Thespesia populnea that had fallen to the ground. These shrubs were native to the pacific basin but have since proliferated to most Caribbean shores. In the West Indies, the fruit of Thespesia populnea, or Portia tree, ripen between May and January. These ripe fruits are used as a food source by the St. Andrew cotton stainers where multiple red bugs from all life stages crowd near one pod to feed on. Juveniles at all instar stages rummage through the leaf litter staying near the adults. Meanwhile, males and females will be attached to one another as a form of mate guarding. During this time, the males will traverse these sandy shores attached to the end of their female partner for up to 4 days.

When food limits are not met, cotton stainers will partake in diapause until there is an abundance of resources to support their offspring. For that reason, it is common to see groups of cotton stainers near beach shores in the Caribbean rather than being dispersed individuals. While it is enjoyable to see this red frenzy on the shorelines of St. John’s Island, the bugs were originally considered to be an agricultural pest, because their droppings would cause tinting on cotton. But the bugs are native to this area of the Caribbean.

If you are interested in true bugs in your area, check out inaturalist.org to find new insects in your community! Can you identify the true bug species that live in Maine?